RCBL Hall of Fame Class of 2012

Special thanks to Lauren Jefferson (HOF Class of 2017) for researching, writing, and producing player biographies.

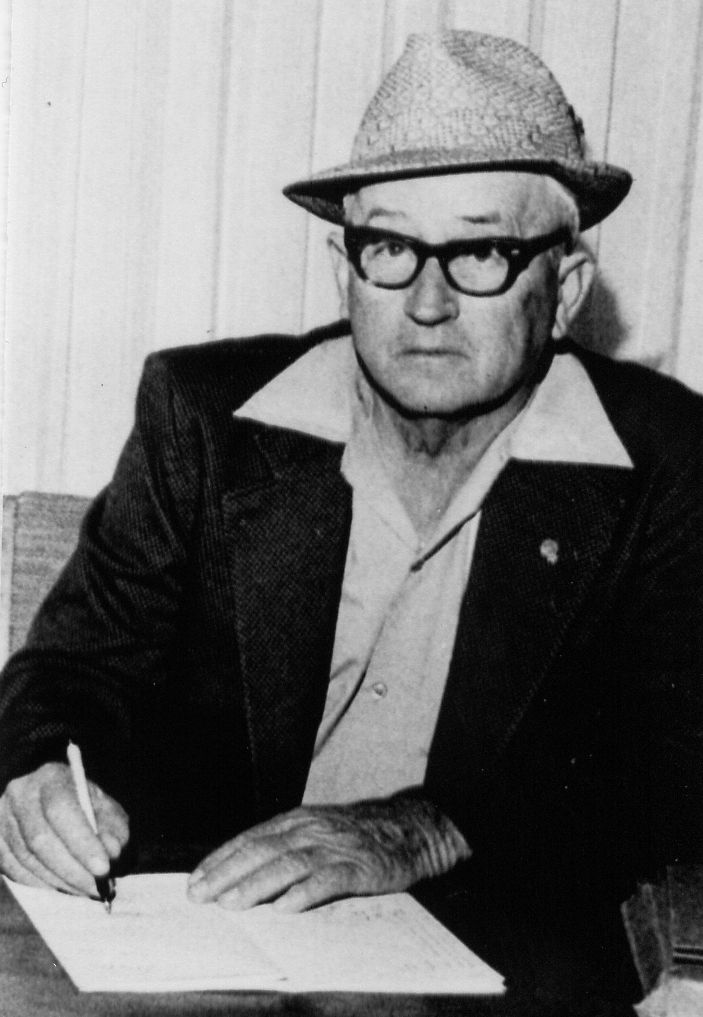

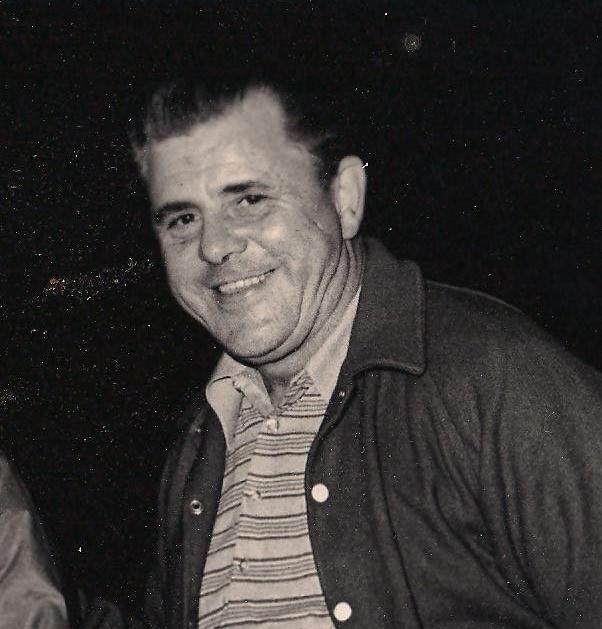

Buck Bowman

Buck Bowman’s name is synonymous with the community and the baseball team he loved best. He was a player first, then a manager for 17 years at Clover Hill. He was instrumental in the creation in 1954 of the Clover Hill Ballpark, the league’s first lighted venue. After his retirement from managing in 1971, the team took his nickname as their own. When he died in 1980, Clover Hill renamed their stadium Buck Bowman Park.

Buck was a farm equipment salesman who was never at a loss for words. There were many times when Bowman, like other devoted managers, single handedly kept baseball alive in Clover Hill. He was persistent and competitive. Sparky Simmons remembers that Buck always had a toothpick in his mouth, a piece of paper and a pencil, and he was “always trying to figure out a way to beat your ass.” Ten runs down with a 3-2 count in the bottom of the ninth, Buck’s favorite saying was: “Only two outs, boys! Only two outs.” He was also remembered for handing out game balls as if they were gold, gathering together the best local talent, using the same signals for his entire career so that everyone knew when the hit and run was on, and perhaps most importantly, treating his players like they were his sons and the fans like they were family. Anyone who has been to Buck Bowman Park on a summer night knows the legacy he has left us. |

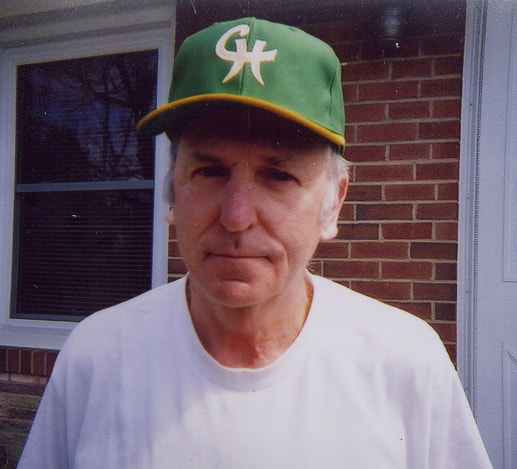

Frank Cline

Frank Cline has spent 50 years as a player and an umpire in the Rockingham County Baseball League. He grew up in a family of six brothers, three of whom played County League. His dad loved baseball so much that a portion of their farmland was given over to a ballfield. Frank played for Mount Clinton High School, then began his career with Ottobine in 1952. He moved with the club to Clover Hill and never left for the next 29 years, with the exception of a two-year stint in the U.S. Army.

Those who played with and against Frank remember that he was a good infielder. During the 1955 season, he and his brother Stanley turned 12 double plays in five games and four in a single game. In one game of the 1956 series against Grottoes, Frank fielded 12 ground balls and 3 pop-ups, making 15 of the 27 outs. Although exact statistics aren’t available, he is known to hold the record for the most hits in the league. According to pitchers who faced him, he was a very tough out. He played at Clover Hill until he was 45, and became an umpire until 2000. |

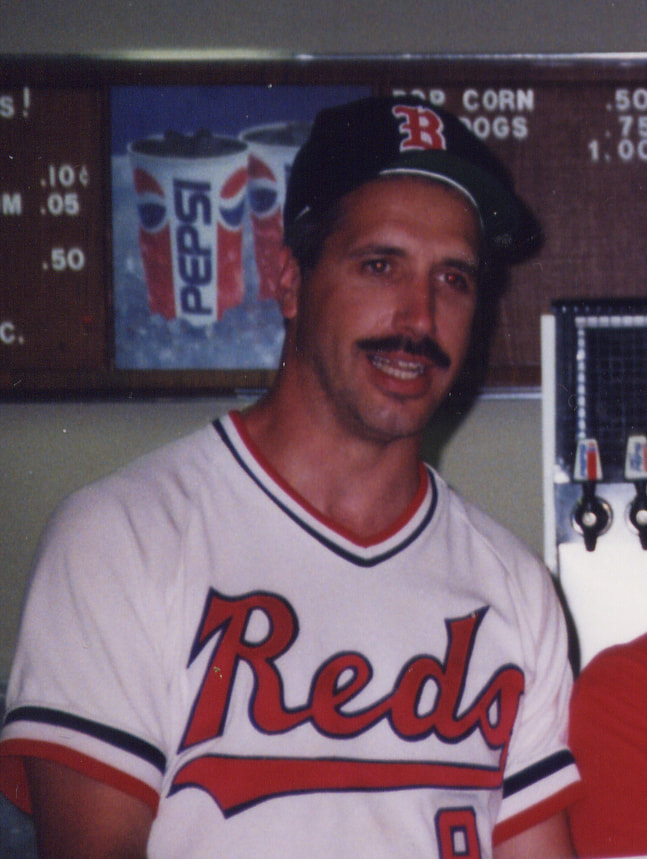

Clint Curry

Clint Curry is known as the RCBL’s premier hitter, but he wasn’t too bad at everything else a baseball player does either. He led the league in home runs for 17 seasons. Though exact statistics aren’t available and wild rumors abound about exactly how many homeruns Clint hit during his career, it is widely agreed-upon that he holds the career league record.

One generally unknown statistic is that he hit 28 homeruns during his rookie season with Clover Hill as a 16-year-old in 1981. Clint will tell you that his first game in the RCBL was against the Shenandoah Indians, who were stacked with former pro players, and that he was scared to death. But he hit a homerun in his first at-bat and felt a little better. After graduating from Turner Ashby, Clint was drafted in the third round and spent three years in the minor leagues. In 1985, he came back to Clover Hill. His talent and hitting ability helped bring fans to the ballparks. Some of what fans say about Clint Curry—that balls he hit just jumped out of the park, that you were on the edge of your seat when he came up to bat—those stories are like what they say about Griff Gilkerson in an earlier era. In fact, Clint hit at least one homerun over the Linville schoolhouse—a feat he shares with Griff. His RCBL career lasted 16 years and included two MVP awards in 1992 and 1993. Most of that time, he played for the Bucks, but he also played for Briery Branch and Linville, helping each team to pennants and series wins. In 2001, a work-related injury affected his vision and ended his career. |

Griff Gilkerson

Griff Gilkerson is among the few Hall of Fame inductees to be selected solely for his athletic feats. Griff was County League’s Babe Ruth. He wielded a bat with pure power and was an excellent defensive player. Many players in Griff’s day thank their lucky stars that he wasn’t using an aluminum bat. Fans came to watch him and the sports writers poured on the adjectives when Griff had a good night. His athletic exploits did much to popularize the league.

Griff began his baseball career as a catcher for Bridgewater High School. He wore a chest protector that had “Thou shalt not steal” written across the front. But he says catching was too much work, so he played first base for most of his County League career, which began in 1952 with Spring Creek when he was still in high school. He moved to Bridgewater in 1955 and was there for the next nine years. Though he surely had many mammoth hits over the years, Griff’s legend comes from three history-making swings. Everyone who was there during those games remembers them and loves to tell the story. The first homerun was during a soggy night at Clover Hill. The next morning, Buck Bowman measured the distance from homeplate to the ball once, didn’t believe his eyes and measured again. Griff had hit it 519 feet. His legend grew during the 1962 playoff series. In 46 at-bats over a nine-game span, he scored 13 runs, drove in 23, and had 20 hits, including nine homeruns. In Game Seven at Linville, he hit two three-run homeruns. The third-inning shot soared into left center and hit the schoolhouse roof. The eighth-inning blast cleared the school and reportedly landed across the road in the parking lot. |

E.L. Knicely

E.L. Knicely managed the Bridgewater Reds for 11 years, from 1984-1995. During that time, the team won nine consecutive pennants from 1988-1996 and eight straight playoff championships from 1988-1995.

Some who knew and watched the Reds of that era will say that the team was stacked with talent and they would be right. There were certainly standout athletes and even former professional athletes on the Reds roster. And there were family ties, too—plenty of Bococks and Knicelys —those family ties made the bonds between teammates stronger. But the qualities that made the Reds so good—their youth, leadership, talent, competitiveness and a little bit of wildness— also made for a volatile combination. It could have been a disaster for E.L, who took over the team at age 24. But it wasn’t. The Reds of those years were an extraordinary team, but they were handled by a man with natural leadership qualities and a knowledge of baseball that demanded respect from players and opponents alike. This is also a man who could have turned his back on the sport after disappointment: an accident at work that impaired his vision and ended his playing days at the age of 22. But E.L. chose to return to the game and to become a different part of history. His best attributes were honest communication and a knack for getting the most out of each individual. His philosophy was that if you weren’t playing for the good of the team, you were playing to the detriment of the team. Every Bridgewater player came to the ballpark knowing their role—and one of those roles was to contribute to a winning team. E.L. is honored for his exemplary leadership through season after winning season, for those winning seasons themselves and for helping to set a standard for what a team of baseball players can achieve in the league. |

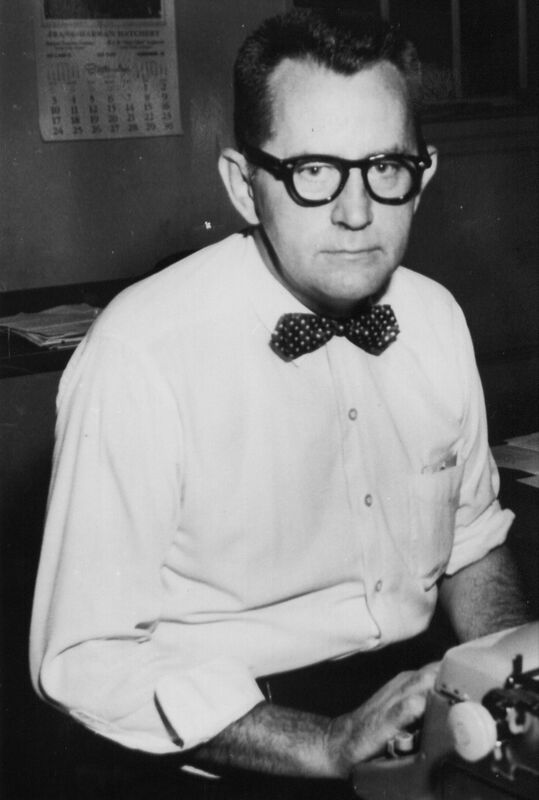

Polly Lineweaver

J.R. “Polly” Lineweaver was a founder of the Rockingham County Baseball League in 1924 and served as its secretary for many years. Polly also worked at the Daily News-Record for 47 years. He got his start as a 16-year-old reporter covering the informally scheduled baseball games between town teams. Sometimes teams didn’t show up, leaving fans in front of an empty field. Players changed teams on a whim. It was easy to bend the rules when there were no rules. And all of that made it tough to be a good sports writer.

Polly was 22 and the DNR sports editor when he threw his support behind the formation of the league. On Saturday, June 28, 1924, the first games were played. Eight teams played a set schedule with regular home games. Teams consisted of local players from designated areas only. Rules guided play. In the following years, Polly occupied several positions at the Daily News-Record, including sports editor. In that role, he always championed the league. |

Lynn Meadows

After the conclusion of his standout career at Elkton High School in 1960, Lynn Meadows thumbed a ride to Grottoes and began his County League career. He became one of the league’s most prolific, outstanding hitters. He spent most of his career at Grottoes, but he also played for Luray, Shenandoah and Elkton, a team he helped resurrect in 1967.

Lynn led the league in homeruns for most of the seasons. He earned MVP honors in 1973. That season, he hit seven home runs in a 10-game stretch. He was a superb clutch hitter and an excellent outfielder. Lynn was famous for his signature weapon, a 36-inch Jackie Robinson bat with a handle as big as the barrel . It took a man just to pick it up, said one former opponent. I would have to put wheels on it to get it to the plate, said another. It’s not surprising that his nickname was Mighty Mite. When he dug into the box, a lot of pitchers probably shared the same thought as Wayne Whitmore did — Pitch it and duck. After his RCBL career was over, Lynn coached both his daughters’ softball teams and umpired Little League and high school games. He also ran the Elkton East recreation center. In the 1980s, he supported a group of ballplayers who were working towards the re-entry of Elkton into the RCBL. For a few seasons, the new Elkton team played their day games at Elkton Middle School and their night games at the old Shenandoah ballpark. Lynn played an instrumental role in securing land for a new ballfield. Stonewall Memorial Park, the home field of the Blue Sox, was created in 1985. |

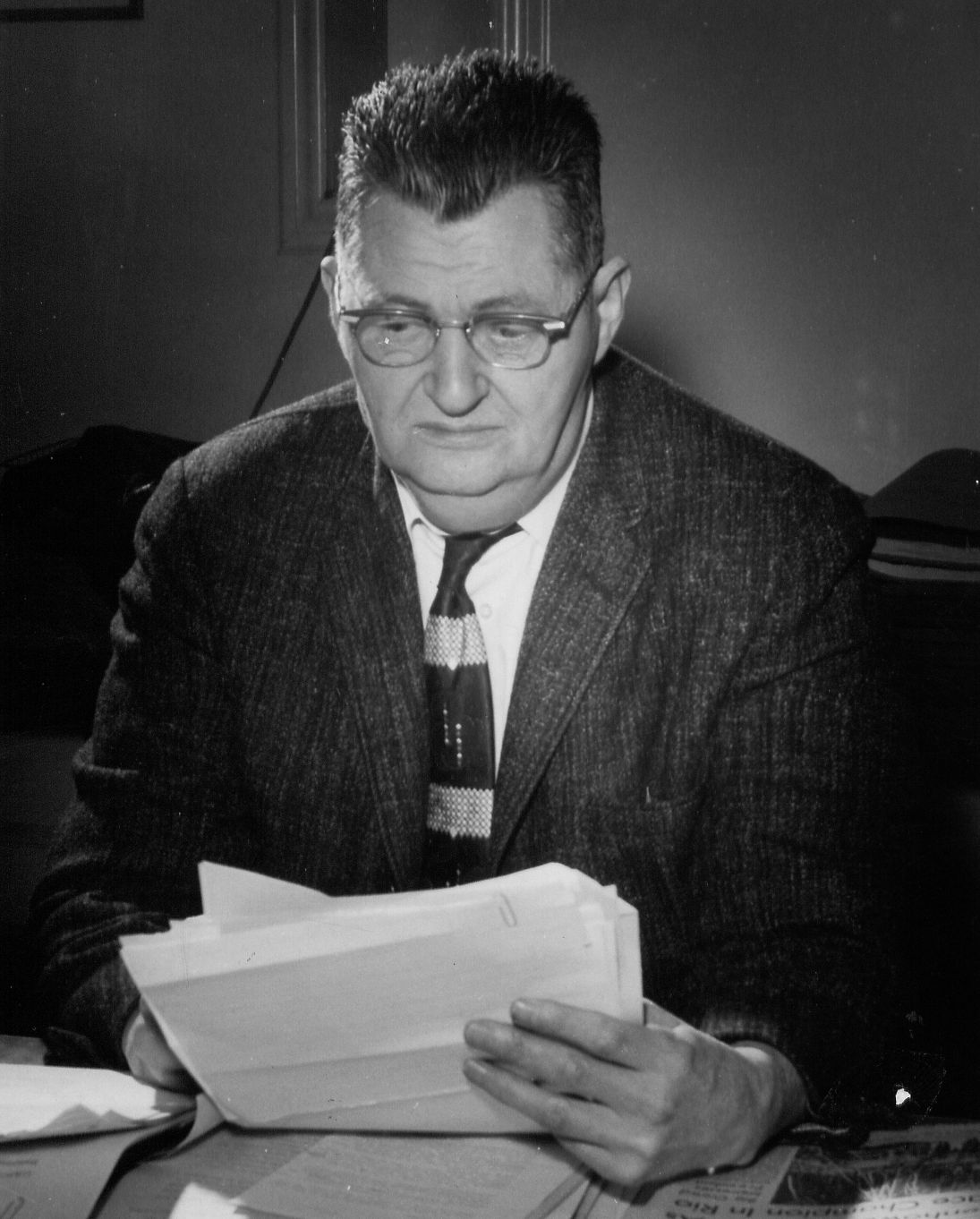

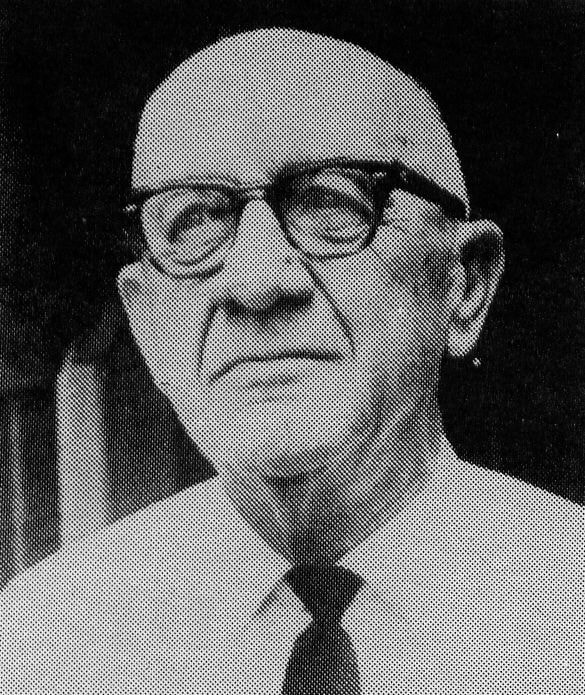

C.C. Michael

C.C. Michael was a tireless, dedicated and selfless advocate for local baseball. A Mount Crawford area native, he was instrumental in forming the Rockingham County Baseball League with Daily News-Record sports editor J.R. “Polly” Lineweaver in 1924, serving as president for eight years. He also president of the Valley League from 1947-1967.Called “Mike” or “Mr. Mike” by his friends, he was also named “the grand old man of baseball” by local sportswriters. In a tribute published after his death in 1971, the last sentence reads: “And should there ever be a ‘Hall of Fame’ for area baseball men, C.C. Michael will stand all by himself.”

C.C. Michael is the RCBL Hall of Fame’s first inductee. |

Karl Olschofka

Karl Oschofka loved the New York Yankees and we’ll forgive him for that because he also loved the Rockingham County Baseball League. Those who knew Karl and worked with him for the betterment and love of amateur baseball in the Shenandoah Valley call him the patriarch of the league. He held every position on the board—secretary, treasurer, vice president/vice commissioner and president/commissioner—and in each capacity, helped to shape and strengthen the league.

A native New Yorker, Karl moved to the Valley when he was 22 years old. He helped his parents manage the Blue Stone Inn, which later became a place where baseball players received first class treatment—whether at the height of dinner hour or after a game at 11:30 at night. By his own admission, Karl wasn’t any good at playing baseball, so he turned his efforts to managing early. Karl helped get the Twin County team into the league in 1964. We don’t know exactly when he became involved on the administrative level, but by 1970, he was serving as vice president. Karl wasn’t solely responsible for every major regulation change, but he helped push through changes to improve the league and to retain its local flavor. The fans were always foremost in his mind. Among the changes during Karl’s tenure were passing through waivers, the free agent rule, the Most Valuable awards, expansion of play-offs to include all teams, changing of the start time for evening games and the return of wooden bats. He pushed for more professionalism from players and umpires. Always diplomatic in his decision-making, Karl wanted nothing more than that the RCBL become the best amateur baseball league it could be. Karl was also a historian. He created three programs, which some of the only literature available about the league. Much of the history shared here today is because Karl knew its value —just as he knew the value of baseball to each of us. Some years, Karl was the only reason County League continued. The only time it’s stopped since 1924 was for World War II. And probably if Karl were living in the Valley then, instead of serving in the Navy, the RCBL would have continued through those years too. We have him to thank for the unbroken history of the post-war RCBL. And he’s one of the major reasons we’re able to come together today on this historic occasion and look forward to other occasions when we can share in the fellowship of baseball. |

Vince Reilly

Vincent Reilly began his career as a sportswriter at the Daily News-Record. He took over from Polly Lineweaver as sports editor in 1947 and continued until his death in 1963. His greatest contribution to County League was to recognize that fans cared about baseball, no matter the level, whether they were watching former minor leaguers, college players, neighbors or family members.

His desk was a hangout where coaches and managers hand-delivered scores and then stayed to talk. When managers called in a game, he didn’t just want the stats, he wanted to know what happened. He supported young athletes and good sportsmanship and conveyed in the importance of sport beyond mere wins and losses. In his columns, Vince was a defender of baseball as a source of civic pride and an outgrowth of the American spirit. He wrote that the purity of the game was preserved by teams like those in the County League and by fans like those who followed their local team faithfully year after year. |

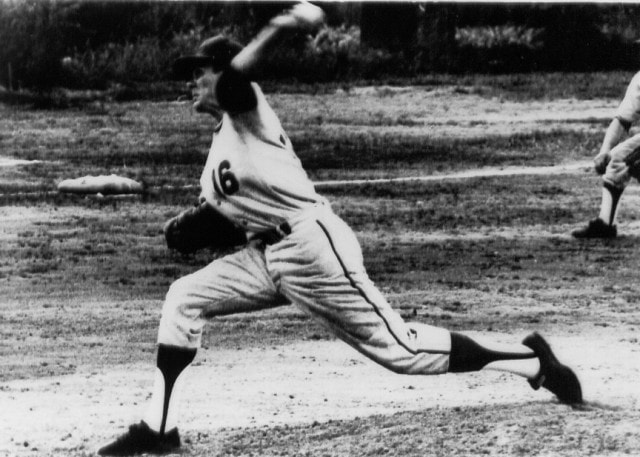

Sparky Simmons

For ten seasons, from 1966-1976, hard-throwing, left-handed Isaac “Sparky” Simmons, Jr., dominated the Rockingham County Baseball League for the Linville Patriots. With mechanics honed in the minors, Sparky brought a level of finesse and control rarely seen on County League fields. His unofficial career record of 134-21 stands as a league record.

Sparky helped Linville be a perennial contender each of those ten years. Linville made eight appearances in the league championships, finishing second six times. In 1972, the Patriots put up a 19-11 record, ending Harriston’s pennant run of seven straight years. Simmons won all 18 games he started and saved five other games, for a total of more than 300 strikeouts. In 1973, the Patriots took the pennant again with a 22-5 record and swept Twin County 4-0 to win the team’s first league series since 1961. Sparky was voted the league’s Most Valuable Pitcher. The Patriots won the pennant again in 1974. He respected anyone who would swing a bat, but you had to prove your ability and your courage first—and then you had to stand your ground. And if you were lucky enough to hit a homerun off Sparky Simmons, you better look out the next time you get in the box. Most of the time, his brother Cricket was his catcher. When that happened, Sparky will tell you, the poor soul who thought he was a baseball player wouldn’t have a chance. The family connection continued with his two sons. In 1976, during Sparky’s final season, his older son Steve was catching when his dad struck out 20 batters in eight innings against the Harrisonburg ACs. Younger son Todd, also a pitcher for the Patriots, was series MVP in 1986. |

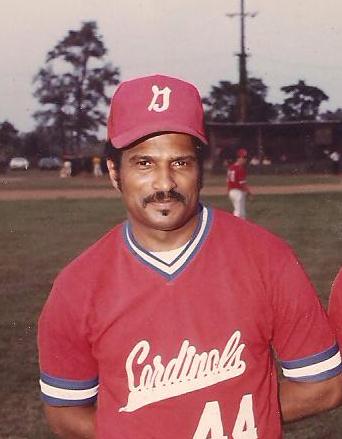

Seymour Solomon

Seymour Solomon, Jr., spent 36 years in the Rockingham County Baseball League as a player and a manager—he was for many years the engine behind the Grottoes Cardinals. But he also changed the league. In the early ‘60s, he and Theodore Temple became the first African-Americans to play in the RCBL. Many of you in the audience were there during those years, and you witnessed the kind of world Seymour and other African-Americans lived in. And you will know that to put on that uniform, sit in that dugout and walk onto that field took a rare combination of courage, dignity, determination and love for the game of baseball. Seymour will tell you that baseball itself was the saving grace of that time. When he got onto the field, everything else fell away. You hear and you don’t hear, he said. And when the game was over, then what he was trying to do, what he was doing, all came back. Baseball is a game of tests, but no test was greater than the one he was living.

Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947. Seymour and Ted did it in the Shenandoah Valley 16 years later. It was a hard road, Seymour will tell you that, not in great detail, but enough to let you know that he needed inspiration to get him through some days. When it got bad, he thought of Jackie Robinson and how much he went through. And he thought of his grandmother, a preacher who taught him to turn the other cheek, to forgive, to move on. After one year at Bridgewater in 1963, Seymour returned to his hometown team in Grottoes, where he remained for all but two seasons of his long career. In 1978, he started managing. That year, the club would have folded if Seymour hadn’t stepped in—and for many years, he was the rock-solid foundation that every ball club needs. He stopped playing regularly in 1979, but recorded his 500th career hit in May 1984. Seymour will tell you he tried to quit —in fact, he wanted to quit—after he reached that milestone, but for one reason or another, he just kept managing—for another 11 seasons. In 1983, the year he received his first Manager of the Year award, his Cardinals won the pennant and the series. In 1995, he was again awarded Manager of the Year honors. That season, the Cardinals had lost three consecutive games in a best-of-seven series against the Bridgewater Reds, who were looking for their ninth straight crown. Grottoes stormed back to win the next four. It was the perfect ending to a great career. |

Bobby Strickler

Bobby Strickler’s association with the RCBL began in 1964, when he managed a team of players from the disbanded Twin County League. By that time, Bobby had been playing baseball in the New Market area for more than 20 years.

Rebel Park became like a second home. In the spring and summer, Bobby’s routine was to come home from work, feed the animals, eat dinner, get in his truck and head to the ballpark. He was always at the field turning on the lights for Stonewall Jackson High School games and RCBL games. Bobby’s vision is visible in just about every aspect of the park. In 1953, he had played an integral role in its redesign and construction. After years of carting bleachers from the high school every season, Bobby built the wooden bleachers and helped with the sunken dugouts in the 1960s. Twin County lasted for nearly 30 years—long enough for Bobby to pass on his love of baseball to three generations. His brother, Jody, played on the team. His wife Nancy served as secretary and treasurer. Their two daughters, Bonnie and Trish, chased foul balls, helped in the concession stand and operated the manual scoreboard. Eventually, his daughters grew up, married and passed their roles on down to their children. After a nearly 20-year hiatus, an RCBL team returned to New Market in 2004. The story is that when Commissioner Karl Olschofka was approached by former Grottoes players Davey Mantz and Kevin Rush about starting a team in New Market, Karl said they would need Bobby Strickler’s permission first. As in the past, Bobby and his family members rallied in support. They have all held positions on the board. His granddaughter Lisa Jones-Hart is one of the first women to serve as a club’s president. |

Harry Whitmore

Harry Whitmore’s lifetime association with RCBL lasted 70 years. He started as a player with Spring Creek in 1938. In 1951, he joined Bridgewater and was involved there for the next 47 years. During that time, Bridgewater earned 16 season pennants and won 13 of 22 series appearances.

Harry, along with manager Pidge Rhodes, was instrumental in integrating the RCBL with the signing of Ted Temple and Seymour Solomon in the early 60s. By 1979, Harry had organized the club’s board of directors and become its first president. He helped put in lights at the field at John Wayland and took responsibility for much of the maintenance of the ballpark. He was also an excellent financial manager and salesman, known among the members of his board for talking notorious cheapskates into making donations. Harry’s love for baseball was passed on to his family. His wife, Geneva, attended every game and his children, Wayne and Diane, don’t remember doing anything else in the summer but chasing foul balls and picking up pop cans at the ballpark. For several years, Wayne and his dad were in the dugout together. Both Harry’s daughter and granddaughter married former Reds players, both of whom are active with the team. Diane’s husband, Dennis, is scorekeeper and bench coach. Denise’s husband, Pat Shiflet, serves on the board. Wayne’s son Richard also played for Bridgewater for 11 years. |